by Sherry Farrell Racette and Cory Willmott

It is no coincidence that members of the Bonga family have been honored and memorialized far and wide in recognition of their accomplishments and lives well lived. They stand as exemplars of Black lives that mattered. The Bonga story begins with the little known and seldom told fact of Canadian slavery. From freed Black slaves in the late eighteenth century, men and women of the Bonga family prospered through four generations. Many of them university educated and trilingual, they pursued diverse occupations and held influential positions within the multicultural fur trade society from Hudson Bay in the north to Pembina in the west and Minnesota in the midwest. By the early nineteenth century, one branch of the Bonga family had become intermarried into the Pillager Anishinaabek of Minnesota. As Rebecca Kugel notes, Anishinaabek considered the Bongas “ethnically French” due to their cultural, linguistic and social affinity with French and métis traders. Yet, as American colonizers forced Anishinaabek into reservations after 1855, growing racism in American society fell heavily on the Bongas and Anishinaabek. Prospects for the more recent generations of Bongas were crushed, illustrating all too vividly the insidious impact of racism.

The Bonga family story challenges the boxes we build in historiography – who is brought forward – who is forgotten. We don’t think about slavery in Canada. We don’t think about indentured servants. We essentialize the genesis of Métis people into a coming together of generic “Indian” women, “European” fur traders and romantic “French” voyageurs, but the events Pierre Bonga played such a key role in are generally viewed as the crucible from which Métis peoplehood emerged. Men of the African diaspora are not included in that history, and yet one the first children born of a fur trader and Anishinaabe woman on the northern plains was his daughter. Pierre, his sons George and Etienne, his grandson and great-grandson – both named Etienne L’Africain – were labourers, interpreters, and entrepreneurs in the fur trade ecosystem. Pierre’s great-grandson, born in Labrador, educated in Montreal, fought in the Civil War before returning to manage small trading posts in the Quebec-Ontario borderlands with his Algonquin wife. As we tease out their stories, the complications and connections grow.

Jean and Marie Bonga: Freed and Thriving

by Sherry Farrell Racette

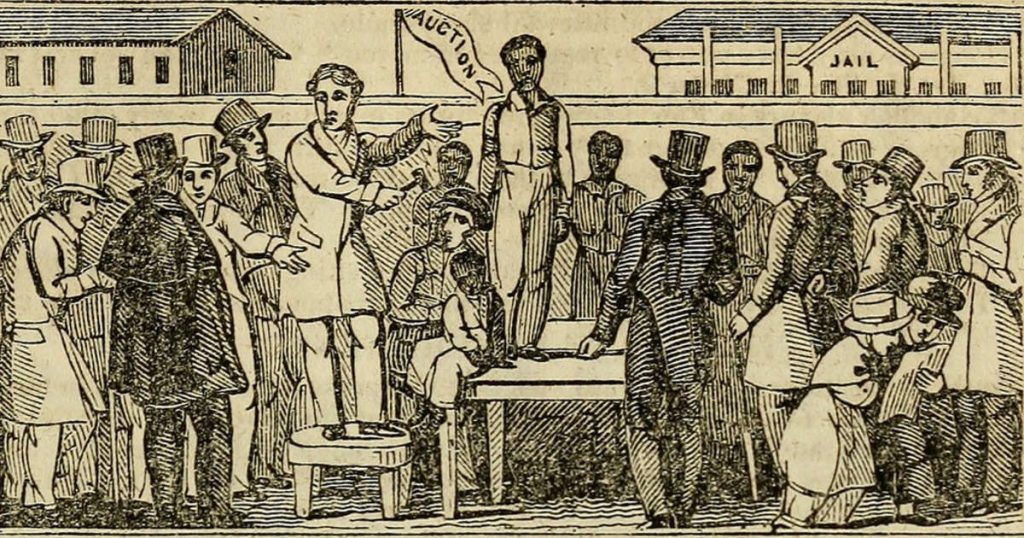

In 1782, Jean and Marie Jeanne Bonga, two Francophone slaves, arrived at Michilimackinac with Captain Daniel Robertson, a British officer taking command of the post. The surname Bonga is common in southern Africa and Martinique, meaning “to give thanks” or “to give praise” in Zulu-Swahili. The origins of Robertson’s ownership of the couple is unclear. He was posted to Martinique in 1762, and both he and his wife’s Montreal family were slave owners.

Jean and Marie Jeanne left a sparse archive. In 1784 Jean Baptiste Perrault described “an old negro named Bonga carrying a load of wet linen” injured after walking into the path of an escaping murderer. At six-year old Rosalie’s baptism in 1786, her parents were described as “a negro … and … Negress living with monsieur Robertson, Captain, commandant”.

In 1787, after leaving his command, Robertson “released” several slaves, including the Bongas, at Mackinac and others in Montreal. The Bongas purchased a house which they transformed into the first regional inn or tavern. In 1794 the couple married and had four children, Etienne (d.1804), Pierre (1777-1831), Rosalie (1782-1834) and Charlotte (1786-1830). Their youngest daughter Charlotte (b. 1786) was baptized on May 4th, 1794. Jean Bonga died the next year (Jan. 20, 1795). Marie Jeanne appears to have returned to Montreal where the family became part of the free Afro-Montreal community.

Etienne, employed as a voyageur, died in Montreal in 1804. Rosalie married John Pruyn, a labourer, in 1806, and a child’s funeral in 1808 identified Charlotte as the wife of Jean Baptiste L’Africain, a carpenter. The Bonga sisters may have formed a Montreal support system for their brother Pierre and his children.

Pierre Bonga: Into the West (ca. 1775 – 1831)

by Sherry Farrell Racette

Born before his parents’ arrival at Michilimackinac, Pierre Bonga began working in the fur trade as a young man, documented with John Sayer’s company at Fond du Lac in 1795, and Alexander Henry the Younger from 1800-1806. Departing from Grand Portage on Lake Superior with the Red River Brigade, Bonga was with Henry in the first canoe, but unlike other men was not assigned a role beyond “my servant” and “negro” suggesting he was a personal servant, rather than an engagé of the North West Company. The brigade traveled to Lake Winnipeg to the forks of the Red and Assiniboine rivers before establishing a fort near present-day Pembina, North Dakota. Bonga married an Anishiinaabe woman of the Pillager band, and in March 1802, Henry wrote: “Pierre’s wife was delivered of a daughter – the first fruit at this fort and a very black one”. Bonga was given increasing responsibility, placed in charge in 1803 during Henry’s absence. In 1806, Bonga was with a brigade sent to “Kamanistiquia” (Fort William) on Lake Superior. Between 1813-1815 he worked as a “middleman” on brigades shuttling between Montreal and Fort William, before having the job of interpreter added to his voyageur duties. In 1815, he filed a last will and testament with a Montreal notary prior to his departure.

Bonga’s physical presence and strength were assets during a period of intense, and increasingly violent competition between rival companies. During a trial seeking damages from North West Company partners for destroying a trader’s camp at Grand Portage in 1802, a “negro” working for Archibald Norman McLeod was among the party, described as tearing and burning “a tent to bits”. In 1803 Henry described an XY Company competitor threatening to kill Bonga, writing with satisfaction that the antagonist “did not escape without a sound beating”. In 1816, Bonga was sent from Fort William to seize a packet of documents from couriers dispatched to Montreal by the Earl of Selkirk. He had become a soldier in the fur trade wars.

Bonga placed his children under the care of the North West Company partners who employed him. They appear in the St. Gabriel Street Presbyterian Church records among the dozens of fur trade children brought to Montreal to be baptized and educated: Etienne Bongo, aged seven (1810), Blanche, aged nine and George, aged seven (1811) were described as children of “Pierre Bongo, in the service of the North West Company, by a woman of the Indian Country”. Their sponsors were Angus Shaw and Archibald Norman McLeod. An older son, 14-year old Jean Baptiste, was engaged as an apprentice to McLeod in 1812. Father and son may have worked together at Fort William, perhaps the “two negroes” observed by Ross Cox among the ethnically diverse crowd in 1817.

After the merger of the North West and Hudson’s Bay companies in 1821, men like Pierre Bonga were made redundant, although HBC Governor George Simpson described him as a member of a large 1822 expedition sent to explore the South Saskatchewan and Bow River region where the Blackfoot and Gros Ventre found his appearance fascinating. Bonga returned to Fond-du-Lac, where he spent the remainder of his career working for the American Fur Company, living comfortably among the Anishiinaabek with his wife and children.

Primary Sources:

- St. Gabriel Street, Presbyterian, Montreal, Ancestry.com. Quebec, Canada, Vital and Church Records (Drouin Collection), 1621-1968 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA, 2008. Original data: Gabriel Drouin, comp. Drouin Collection. Montreal, Quebec, Canada: Institut Généalogique Drouin.

- Last Will and Testament, Pierre Bonga, May 1815, Répertoires de notaires, Montreal, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Quebec, 62.

- Name Index: NWC Records, Account Books (1795-1827) online index https://www.gov.mb.ca/chc/archives/hbca/name_indexes/nwc_accounts.html Pierre Bonga NWC Ledger nd. F.4/32 fo. 95.

Secondary Sources:

- Cox, Ross, The Columbia River or Scenes and Adventures during A Residence of Six Years on the Western Side of the Rocky Mountains, Vol. 2 (London: Colburn and Bentley, 1831), 293.

- Gough, Barry, The Journal of Alexander Henry the Younger 1799-1814 Vol. 1: Red River and the Journey to the Missouri (Toronto: Champlain Society and University of Toronto Press, 1988).

- Harper, Mattie M. (2012). French Africans in Ojibwe Country: Negotiating Marriage, Identity and Race, 1780-1890. UC Berkeley. ProQuest ID: Harper_berkeley_0028E_12661. Merritt ID: ark:/13030/m5r2157g. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1zm0f6rt

- Mackey, Frank, Done with Slavery: the Black Fact in Montreal: 1760-1840 (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2010): 198-199.

- Morrison, Jean, Superior Rendezvous-Place: Fort William in the Canadian Fur Trade (Toronto: Natural Heritage Books, 2007), 109.

- Nute, Grace Lee, “A British Legal Case and Old Grand Portage”, Minnesota History 21, no. 2 (June 1940): 127-128.

- Simpson, George, An Overland Journey Round the World: During the Years 1841 and 1842 (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1847), 58.

George Bonga (1802-1874) – A Life of Trading, Translation and Transition

by Cory Willmott

Born into the heart of the Great Lakes fur trade at the St. Louis River, current day Duluth MN, George grew up fluent in English, French and Anishinaabemowin. This skill laid the foundation for his life of trading and interpreting for the first three quarters of the nineteenth century. After gaining an education in Montreal, he entered the fur trade as a voyager at an early age. In 1820, the 18-year-old George served as interpreter to Lewis Cass on his search for the headwaters of the Mississippi at Lake Itasca. He worked for John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Company, where his strength and ability helped him rise quickly through the ranks. In 1830, he became a licensed trader in Leech Lake, Otter Tail Point and Platte Lake. The missionary Edmund Ely, stationed at Fond du Lac, provides first-hand insight into George’s daily life in the 1830s. With other prominent traders, he travelled throughout Minnesota carrying goods, furs and information. George also participated in mission services and helped to arrange meetings with chiefs. Ely benefited from his endorsement and praised his interpreting ability. Rev. Henry Whipple also praised George, writing that “No word could be better trusted than that of George Bonga.” Also having the trust of the area’s traders, when William Aitkin’s son was fatally shot by an Anishinaabe man, he asked George to track him and bring him in. This George did in the dead of winter, after the initial search party failed. Ironically, he was acquitted because young Aitkin was mixed blood.

During the 1840s, George and his Anishinaabe wife, Ashwewin, had their first child, James (b.1841), followed by Peter (1847-1914), William (1850-1909), Susan (1852-1939) and Georgeance (“Little George” 1868-1930). In the 1850s, George worked for the Leech Lake Indian agent, serving as interpreter and superintendent of the government farm. By the 1860s, he reimagined himself as a “Dry Goods Merchant” to keep up with the changing face of retail in the sedentary reservation lifestyle. He was among the wealthy half-breed traders who settled at Leech Lake, acquiring real estate and doubling his “personal worth” from $2,000 in 1860 to $4,000 in 1870. He was the third wealthiest person at the agency, only surpassed by the brother of the Indian Agent and the town’s physician.

In 1867, Bonga was among the interpreters who helped negotiate the treaty that created the White Earth reservation. In the spring of 1868, conflict broke out between the Gull Lake chiefs Gwiiwizens (Hole-in-the-Day II) and Waabaanakwad (White Cloud) over when to move there. George wrote Bishop Henry Whipple that Gwiiwizens was “playing his old hand (when he does not get good money) in an underhanded way to try to prevent the Indians from going [to White Earth] only when he thinks proper.” Through none of George’s doing, Gwiiwisens was murdered a few weeks later, and some years later George’s son William joined Waabaanakwad’s followers at White Earth. George’s offspring married among prominent Anishinaabek and métis families, thereby consolidating and continuing their prosperity into future generations. George’s lifelong allegiance to Anishinaabe leaders who favored assimilation will remain contentious, but his personal success as an African American entrepreneur and diplomat can never be disputed.

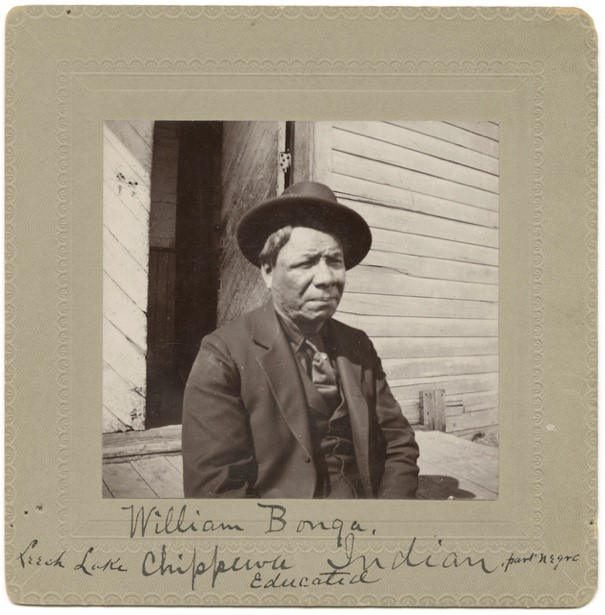

William Bonga (1850-1909) – A Life Among the Reservation Elite

by Cory Willmott

William Bonga’s childhood years were spent near the government establishment at Leech Lake Reservation, where his father, George Bonga, was superintendent of the government farm. He attended school there with his younger sister, Susie, while his older brother, James, worked as a farm hand. Sela G. Wright, who oversaw the farm, had been sent by a missionary outcropping of Oberlin College, a liberal arts university that promoted the abolition of slavery. Young William was coming of age after the massive land cessions of the 1855 Treaty of La Pointe put an end to the fur trade economy. In 1866, he was 16 years old when the first permanent agency buildings went up at Leech Lake.

By the 1860s, William’s former fur trader father had left the farm and entered the mercantile business. Brother James was working for him as a clerk. In 1868, corrupt government agent, Charles Ruffee, with his associates John G. Morrison and Clement Beaulieu, hired a group of Leech Lake warriors to assassinate the famous Gull Lake chief, Gwiiwizens (Hole-in-the-Day II). The head chief at Leech Lake, Nigone Benais (Flat Mouth II), refused to hand the assassin warriors over to authorities. As a member of Nigone Benais’ band, these events must have formed a lasting impression on William. In 1870, he and another former fur trader’s son were boarding with Sela Wright’s wife at her home in Lorain, Ohio, while attending Oberlin College.

(MNHS E97.1B r7 (Locator Number)

14252 (Negative Number)

Returning to Leech Lake, William found a budding lumber town with a hotel and tavern. It was overrun with civil engineers in the initial planning stages of building a series of dams that would aid the transport of lumber while flooding Anishinaabe subsistence resources. While this was developing, William married Enimwekway (Nettie) and they had their first child, Equasaince, the same year that his father died (1874). The couple had three more children, Odanah (Mary) in 1877, Simon John in 1880 and Joseph in 1885. That same year, tensions over the government dams came to a crisis with plots to assassinate Nigone Benais, which drove him out of town. William is reported saying he would “raise the tomahawk” if the issue were not settled, possibly in his role as a private in the newly appointed Indian police force.

His mother died in 1889, and his family joined the Leech Lakers who accepted allotments at White Earth. Joining Waabaanakwad’s (Chief White Cloud AKA D.G. Wright) advance guard of 1868, William moved his family to White Earth in 1890, although they did not inhabit the allotted plots until 1900. Now a government interpreter, William wrote numerous letters advocating Anishinaabe treaty rights. In 1899, he and his cousin Paul Bonga were interpreters for a delegation to Washington led by Nigone Benais, who had returned to Leech Lake in the aftermath of the Bear Island War in which an estimated handful of Anishinaabe warriors triumphed over three hundred US armed forces.

From 1890 until his death in 1909, William lived and worked at White Earth with his wife and children, close to the Indian agency and surrounded by other prominent Anishinaabe and métis families, such as the Wrights, Warrens, Roys, and Bellangers. Ethnically Anishinaabe or métis, the foremost culture wars of his lifetime were those among Anishinaabek, métis and whites, not between whites and blacks.

Primary Sources:

- Census and other data assembled by Cory Willmott in The Bonga Family Tree on Ancestry.com: https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/tree/169689047/family/familyview?cfpid=212197924522&selnode=1.

- Treaty with the Chippewa of the Mississippi, March 17, 1867 (https://www.firstpeople.us/FP-Html-Treaties/TreatyWithTheChippewaOfTheMississippi1867.html, Accessed June 20, 2020).

Secondary Sources:

- Bigglestone, William E. 1976. Oberlin College and the Beginning of the Red Lake Mission. Minnesota History 45(1): 21-31.

- Brown, Curt. 2015. MN History: Unflappable fur trader was at heart of state’s first murder case. Star Tribune, April 14 (https://www.startribune.com/unflappable-fur-trader-was-at-heart-of-state-s-first-murder-case/299456961/, Accessed June 20, 2020).

- Diedrich, Mark. 1999. Ojibway Chiefs: Portraits of Anishinaabe Leadership. Rochester, MN: Coyote Books.

- Ely, Edmund F. 2012. The Ojibwe Journals of Edmund F. Ely, 1833-1849. Theresa Schenck, ed. Lincoln, NB: University of Nebraska Press.

- Kugel, Rebecca. 2007. “Leadership within the Women’s Community: Susie Bonga Wright of the Leech Lake Ojibwe.” In Native Women’s History in Eastern North America before 1900: A Guide to Research and Writing. Rebecca Kugel and Lucy Eldersveld Murphy, eds. Pp.166-200. Lincoln, NB: University of Nebraska Press.

- ——- 1998. To Be the Main Leaders of Our People: A History of Minnesota Ojibwe Politics, 1825-1898. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press.

- Treuer, Anton. 2011. The Assassination of Hole in the Day. St. Paul, MN: Minneapolis Historical Society Press.