by Karl Hele

League of Indians Founding at Sault Ste. Marie

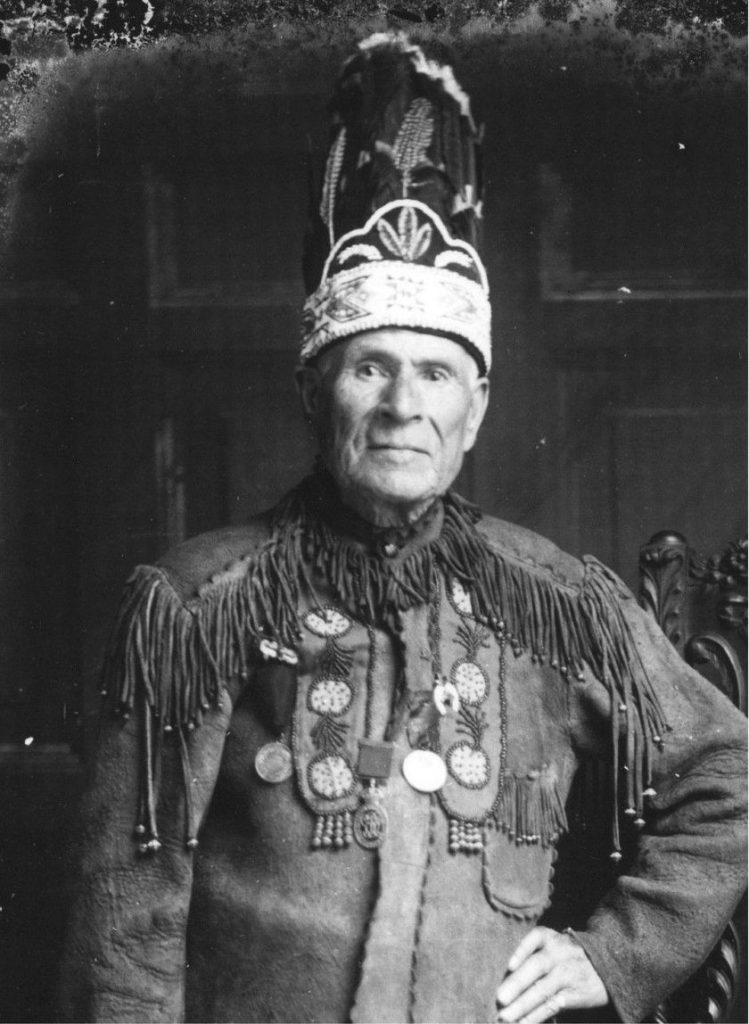

On 4 September 1919 more than 30 Chiefs assembled at Sault Ste. Marie’s YMCA to draft a constitution along with Frederick Ogilvie Loft for the League of Indians. During the meeting Loft and the Chiefs attempted to present the future King Edward VIII, who was visiting the Sault, with a petition. The League, according to Loft, wanted to address Parliament directly, see improvements in First Nations’ education and health care, as well as establish Indigenous control of reserves and recognition of treaty rights. Delegates to the convention also critiqued Indian Affairs’ abuse of powers. Indian Affairs through its agent at the Sault denied that the League spoke for Indians. Others agents attempted to associate the League with the ‘radical left’ of the day – the Bolsheviks. Regardless, both demands of and opposition to the League of Indians foreshadowed modern day conversations about Aboriginal and treaty rights. The League of Indians disappeared by the 1930s, but its last official vestige became the Indian Association of Alberta (IAA). The IAA then went on to be a key founder of the National Indian Brotherhood and subsequent Assembly of First Nations. Hence, the League did represent the voice and interests of First Nations.

Recent Court Decision on Enfranchisement from 1951 to 1985

On 31 July 2020 the Quebec Superior Court in Montreal ruled that the Indian Registrar’s application of voluntary enfranchisement to single unmarried Indian women from 1951 to 1985 was erroneous. This case arose out of the denial of application for registration based on the rational that the child’s grandmother had voluntarily enfranchised under the terms of the Indian Act, specifically section 108(1) in 1965. During the submission process and the verbal arguments it became apparent that the modifications to registration reinforced or codified the enfranchisement provisions pre-Bill C-31 though the various clauses of section 6 of the modern Indian Act. Justice Barin held that in denying the application the Registrar “in a way required the Indigenous peoples of Canada and Canadian society at large to continue to assume the unfortunate consequences of an undesired past.” This decision, if the Crown does not appeal, will help many women who were incorrectly allowed to voluntarily enfranchise between 1951 and 1985. It also potentially sets a precedent or a guideline for judges interpreting the application of the Indian Acts’ provisions – for one must assume that “the legislature says what it means and means what it says”.