by Bradley Clements

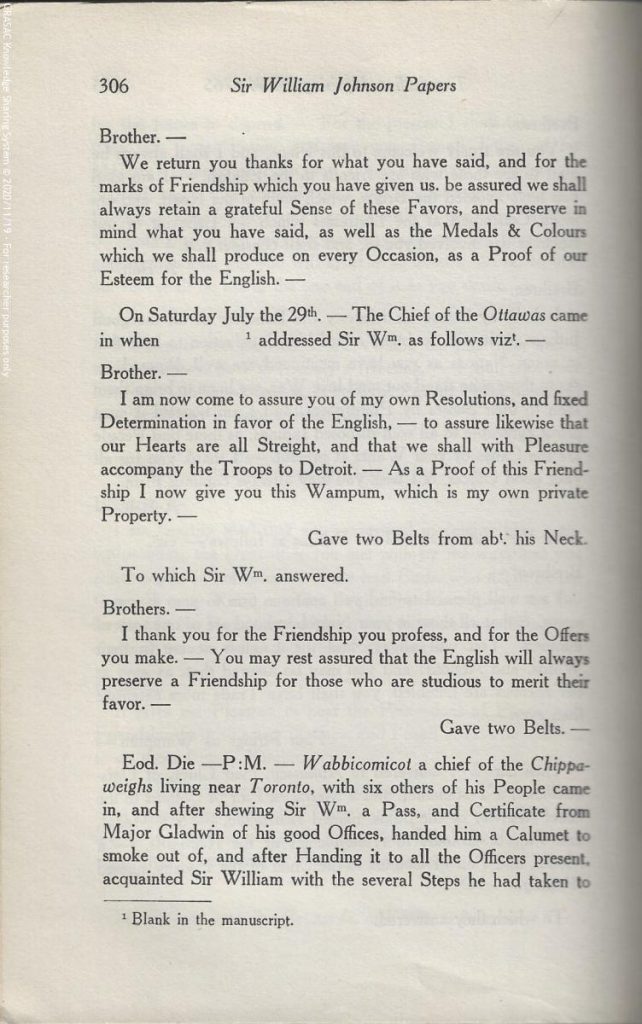

Niagara Congress Minutes, July 28, 1764. In “The papers of Sir William Johnson, Volume 11,” prepared for publication by the Division of Archives and History, pg 303-307. Albany: University of the State of New York, 1953. GKS ID: 58857.

Last month, many questioned and challenged “Canada Day” as the celebration of a colonial and genocidal state. July 1 was designated as the date of Canadian confederation by the 1867 British North America Act. This Act also unilaterally asserted Canada’s jurisdiction over “Indians and lands reserved for the Indians,” the legal rationale for much colonial violence that followed.

Some have argued, though, that the colonial claims of confederation be rejected as the bases of settler presence in northern Turtle Island, suggesting a turn to the Treaty of Niagara: “the most ‘fundamental agreement’ yet entered into between First Nations and the Crown, and much more than a unilateral declaration of the Crown’s will,” according to John Borrows (1997, 169). During July of 1764, approximately 2,000 people from 24 Indigenous nations travelled from as far as the Mississippi, James Bay, and the Atlantic to Niagara where they negotiated a relationship with the British Crown. Reciprocal responsibilities were agreed upon, sanctified, and represented by various wampum belts, such as the 24 Nations Belt and the 1764 Covenant Chain Belt. The gathering and negotiations concluded on August 1.

As a settler Canadian I wonder what it might mean to commemorate August 1 and uphold the mutual sovereignties, responsibilities, and relationships recognized 257 years ago, rather than July 1 and the unilateral imposition that it represents?

The publication of the council minutes from the Treaty of Niagara pictured above is one of the few items that I could easily identify in the GKS related to this event. However, this agreement is most pertinently recorded in wampum belts, as referenced in the text. Recuperating wampum and other treaty items in museums is one important role that GRASAC artists and researchers (and partners in projects such as On the Wampum Trail) play in reconnecting material heritage with their diverse and important relationships.

References:

Borrows, John. 1997. “Wampum at Niagara: The Royal Proclamation, Canadian Legal History, and Self-Government.” In Aboriginal and Treaty Rights in Canada: Essays on Law, Equity, and Respect for Difference, ed. Michael Asch. Vancouver: UBC Press.

Hele, Karl. 2011. “Treaty of Niagara, 1764.” The Canadian Encyclopedia.