A GRASAC Profile Article

Aaron was interviewed by Kate Higginson in April 2017

One of the things that had the biggest impact for me [as a GRASAC RA] was being brought into a professional relationship where [experts in the field], who I respect so much, were willing to take me seriously as a student. We could have real conversations and they would listen and value my perspective in a way that doesn’t happen in your average law school classroom…

In this profile we look back almost a decade at one of GRASAC’s earliest Research Assistants. In 2008, Aaron Mills was an undergraduate student in law at the University of Toronto, where he was hired by two of GRASAC’s founders, Darlene Johnston and Heidi Bohaker, to study records of early treaties in southern Ontario and add information about them to the newly created GRASAC database. One memorable part of his time as an RA was travelling with other GRASAC researchers to Ottawa to document a collection of Wendat heritage items at the Canadian Museum of Civilization.

Aaron (Waabishki Ma’iingan) is a Bear Clan Anishinaabe from Couchiching First Nation (Treaty #3 territory) and from North Bay, Ontario (Robinson-Huron Treaty territory), and he has continued over the past decade to contribute significantly to the field of Indigenous Law. His scholarship focuses on “the importance and the stakes of revitalizing our own Anishinaabe systems of law within our own constitutional orders.”

At the heart of my [PhD research] is the idea that indigenous peoples, like all peoples, are free only when living under systems of law that reflect their own deep norms—for instance, their ideas about freedom, justice, and equality—which they have authorized as legitimate. Because Canadian constitutionalism disallows this basic freedom for indigenous peoples, it has institutionalized a relation of domination, the violence of which impacts all Canadians, not just indigenous peoples. Colonialism isn’t a completed historical fact; it is a relational mode and it is thriving. I believe the only way to decolonize our relationship is to empower the revitalization of indigenous legal orders. Healthy indigenous legal orders stand to benefit us all.

While at the University of Toronto, Aaron served as editor-in-chief of the Indigenous Law Journal and sat on the board for Aboriginal Legal Services of Toronto. He then went on to earn an LLM from Yale Law School and is currently finishing his doctorate in Law at the University of Victoria, where he is working with another of GRASAC’s founders, John Borrows, who, in turn, has described Aaron as “one of the most creative, innovative and thoughtful students I have taught in my 25 years as a law professor.” Aaron’s scholarship has received numerous awards, including a Trudeau Foundation Scholarship, a Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship, and a Talent Award from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. We offer our congratulations to Aaron on his recent appointment as an Assistant Professor of Law at McGill University!

As a GRASAC Research Assistant, Aaron’s main task during the summer of 2008 was to study the Daniel Claus Fonds (on loan from Library and Archives of Canada, MG19) and to add any relevant information on southern Ontario treaties to the GRASAC Knowledge Sharing System (GKS). Aaron remembers long hours reading through these files on microfilm in Robarts Library, looking for references to annuity payments and the Treaty of Niagara, and taking digital images of relevant slides since these files had not been digitized yet. This “fairly isolated and solitary endeavor,” was punctuated by meetings with Heidi to discuss findings and the meta-issues that arise in this type of historical work: the related historical context for these documents, the symbols used as shorthand writing conventions in this period, or how to code and classify things in the GKS.

It was a constant, relentless struggle” to decipher these old hand-written filmed texts and Aaron jokes that “fortunately my own writing is absolutely abysmal, so my eye is trained to recognize script that looks just like squiggle!

Every once in a while there would be an exciting find that contributed to a larger reflection or understanding and Aaron remembers how he could see the GRASAC project growing in these particular moments. Aaron’s careful work in the archives that summer led him to create a whopping 150 new records in the GKS!

There was one particular trip [to the Canadian Museum of Civilization] that really stood out for me because it made available a kind of opportunity that otherwise wouldn’t have been (and since hasn’t been actually) available to me to access the archives and lab spaces where material analysis is done…

In June 2008, Aaron was part of the GRASAC research team that travelled to Ottawa for a week to study collections at Canada’s Museum of Civilization (now the Museum of History). In keeping with GRASAC’s commitment to interdisciplinarity, holistic understandings, and respecting both Indigenous and Western ways of knowing, members of this GRASAC research team came with a diverse range of expertise to share:

- Aaron Mills (Law, University of Toronto)

- Anne de Stecher (Art History, Carleton University)

- Darlene Johnston (Law, University of British Columbia)

- Heidi Bohaker (History, University of Toronto)

- Jameson Brant (Aboriginal Training Program, Canadian Museum of History)

- Janis Monture (Director, Woodland Cultural Centre)

- Jonathan Lainey (Historian, Library & Archives Canada)

- John Moses (Repatriation, Canadian Museum of History)

- Judy Hall (Curator, Canadian Museum of History)

- Ruth Phillips (Art History, Carleton University)

- Stacey Loyer (Art History, Carleton University)

Getting to see and engage with coats and bags and you-name it was pretty incredible. Much of the material was Wendat on this occasion… Just to be able to connect with it was incredible.

While the GRASAC team studied the collections at the CMC, Aaron recalls that “a fascinating dialogue ensued around the table… it was an amazing education to see people’s expertise on display, to see points of agreement and disagreement, and it hit home to me the nature of professional interactions – because [then as] a student I hadn’t had [the chance] to see how professionals actually interact and exchange with one another. So as a student it was an honest privilege to be able to bear witness to that.”

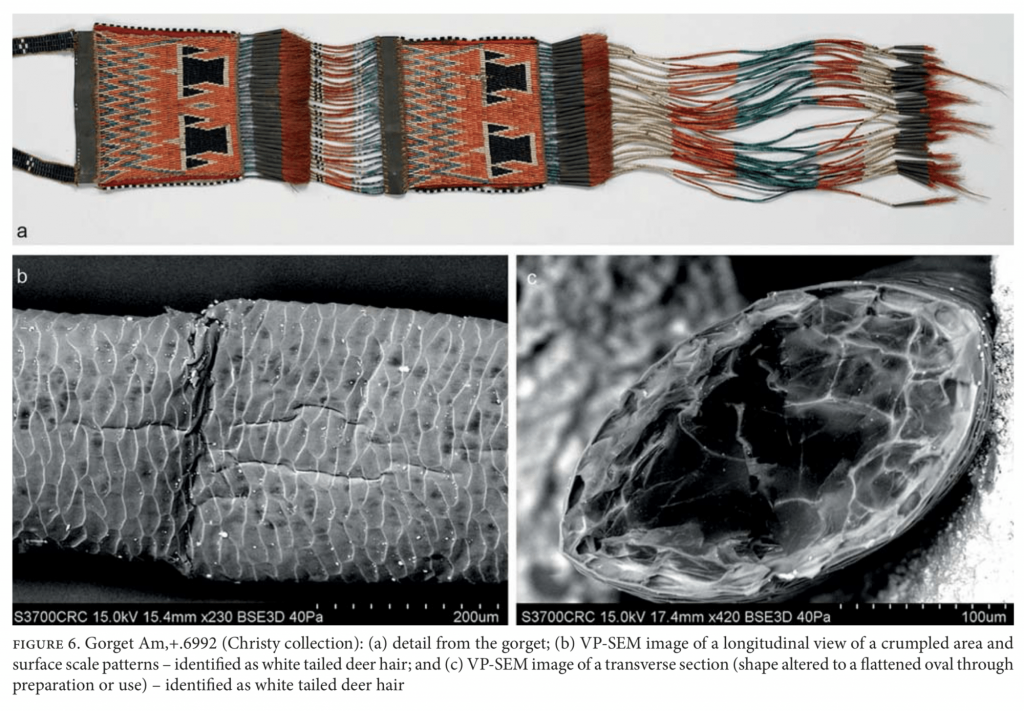

When an item adorned with hairs of an unusual thickness was examined, Aaron remembers Ruth and Darlene trying to decide whether it could be made with fine porcupine quills or thick moose guard hairs. Being at the CMC, they were able to delve further into this question by using the museum’s high powered microscope to zoom in on the individual fibres.

To see that that kind of debate play out and to see how it was handled was fascinating.

Indeed, these debates at the CMC, and similar ones during the GRASAC team trip to the British Museum in 2008, provided the impetus for GRASAC members Judy Hall (Curator of Ethnology, Eastern Woodlands, Canadian Museum of Civilization) and Jonathan King (Keeper of Anthropology, British Museum) to launch more in-depth research into these questions by, respectively, partnering with the Canadian Conservation Institute and utilizing variable pressure scanning electron microscopy to analyze the types of animal hairs used to make numerous Great Lakes items in their collections. Below is an example of one of the amazing microscopy images that resulted and you can read Jonathan King and Caroline Cartwright’s full report online: “Identification of hairs and fibres in Great Lakes objects from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries using variable pressure scanning electron microscopy” (The British Museum’s Technical Research Bulletin, Volume 6, 2012).

Reflecting back on this research trip, Aaron explains that “it also helped me to realize that as my own knowledge grows, my voice actually counts… Because [the team] often thought differently from one another it really painted a veneer of reality over information that in a textbook by any one of these folks I respect so much would come off as a little more matter-of-fact. So I realized what a strong role agency plays in academia and that was really helpful too.”

This research trip offered the chance to learn about protocols and ethics surrounding sacred or sensitive belongings or beings; including which of these GRASAC ought or ought not to document and how and why. One day, working with a heritage bag selected from the collection, everyone was shocked to find a necklace made of human bone tucked away, unlabeled, inside the bag. “So there was a huge human remains issue,” Aaron explains. “But it was a real eye-opener for me to see how respectful everyone was and the deep commitment to getting it right that everybody had. Everyone immediately knew how serious this was, and they all handled it so respectfully… It was a powerful moment and it has always stood out for me.”

One of the most memorable parts of working with GRASAC as a student, Aaron notes, was the chance to be part of a circle of diverse and respected knowledge holders who were working together to share insights and create new understandings. To be included in this dialogic and collaborative research process – with its free flowing debates – was empowering. Aaron remembers how the team “spoke more openly, more freely, they were less guarded: if they had general queries they weren’t afraid that it would look like they might not know everything. They were open and thinking things through. So the humanness of that was amazing: to be respected in that way, to be allowed to hear and participate in that was very validating.”

Chi miigwech, Aaron, for all of your contributions to GRASAC!

Learn More About Aaron’s Work:

- Biography: Profile of Aaron for his SSHRC Talent Award (given to a single humanities or social sciences student in Canada each year). “My work seeks to articulate a form of governance that allows diverse Indigenous and settler peoples on Turtle Island (North America) to live with one another and with (and, critically, through) the earth, in a good way. Acknowledging that colonialism stands in the way of this respectful relationship—that colonialism is a relationship, not a long-completed fact, and thus that it persists today—isn’t prioritizing the past over the present. It’s prioritizing a non-violent future for all peoples of Turtle Island over the quiet violence of Canada’s present.

- Biography: Profile of Aaron on the Trudeau Foundation Website “Aaron Mills’ research discloses a view of Anishinaabe constitutionalism grounded in an Anishinaabe worldview. The cultural grounding is imperative to his research because it presents an opportunity to understand what matters most to Anishinaabeg communities, and why. With this understanding, settler peoples are empowered to forsake existing relationships premised on domination for functioning treaty relationships through which both indigenous and Canadian political communities may thrive. To this end Aaron works in various capacities with indigenous elders and knowledge keepers, indigenous communities, lawyers, judges, academics, students, media, NGOs and public service institutions, and engaged members of the general public.”

- Video Lecture: Aaron Mills, “Belonging and Mutual Aid.” The Walrus Talks Conversations about Canada: We Desire a Better Country series has asked youth leaders and members of the Order of Canada across the country how they would perfect the idea of Canada (15 May 2017). “There is a form of governance inherent in the earth itself – the earth way – which all other forms of creation know and follow. Life beyond the boundaries of human communities is inherently lawful and orderly and a good relative learns to fit in.” And the beautiful conception of “community as a constellation of gifts.”

- Scholarly Article: Aaron Mills, “Aki, Anishinaabek, Kaye Tahsh Crown.“ Indigenous Law Journal 107 (2010): “In theorizing the Anishinaabe law relevant to natural resource development, this paper engages the causes and results of these conflict of laws scenarios and seeks to allow for new options for natural resource development, both peaceful and respectful, on Anishinaabe territory. Ultimately, resolution of these conflicts turns on what sort of a relationship Canada wants with indigenous communities. In the context of natural resource development, if we all want to get along, external recognition of and engagement with indigenous law is a necessity.”

- Podcast: “Tsilhqot’in and Aboriginal Title: A Path to Reconciliation?” This episode of the McGill Law Journal Podcast explores the potential impact of the Tsilhqot’in decision on three distinct groups of actors: first peoples, government and commercial actors. We interview Professor Kirsten Anker, Aaron Mills, and Caroline Briand. (October 2014)

- News Article: Aaron Mills, “To all my relations: Contemporary colonialism, and treaty citizenship today.” Rabble News. (August 14, 2014): “The Treaty of Niagara, 1764, through its turn to Indigenous legal traditions, created an alternative that allows us to reject contemporary colonialism and yet which allows all of us to legitimately call these lands home. Instead of waiting for Canada to decolonize itself, it is for each of us as citizens of a shared political community to pick up this Treaty, practise it, and live it.

- News Article: Aaron Mills, “An open letter to all my relations: On Idle No More, Chief Spence and non-violence.” Rabble News (January 10, 2013): “I am writing to you, all my relations Indigenous and other, because in all I have seen and felt in 31 years, now is the most afraid I have been for you and for myself, the most ashamed I have been of my Prime Minister and of my Governor General, and the most proud I have been of my Indigenous relations and so importantly, our settler allies who have surprised and amazed me. I am humbled by their good words and actions.”